The joys of messaging without a message bus

Summary

Depending on the usecase, it’s possible to build a production-grade, near-realtime messaging system on top of just PostgreSQL, foregoing messaging middlewares such as Kafka entirely. This will take a certain amount of care, so while it can be simple it might not be that easy. After all, you’d be venturing off the beaten path.

The cost of Kafka and similar software, in terms of operation, complexity and financial overhead is non-negligible, which is what prompts us to look for an alternative.

We propose an architecture and sample implementation (in Scala) which might be a good fit if

- You haven’t already invested in a messaging bus

- You already run PostgreSQL

- Your throughput requirements are far from Google scale - which, statistically speaking, they are.

If the above description does not fit your usecase, you might still find this article a useful exploration in system design.

Introduction

With some spare time on my hands, I was looking for a project to brush up on my programming and system design skills, and get experience with Scala 3.

My initial pick was an OAuth / OpenID Connect server implementation. After faffing about with documentation for a week, I started to drown in the 20-ish RFCs involved and realised this would take me around three years, bankrupt me completely and I’d probably lose my ability to communicate with humans in the meantime. For the sake of my financial stability and mental health, I needed a less ambitious goal.

That auth server I had abandoned would have required a communications service - at the very minimum, something capable of sending emails for tokens, password resets, security notifications and such. It’s an extremely common and well understood piece of infrastructure, so I decided to go with that.

In a comms service, the actual email sending is performed by a SMTP-capable server. It’s an interesting topic in itself, since hosting an SMTP server in 2025 that’s actually able to deliver email to people and not get rejected or flagged as spam is a surprisingly complicated endeavour. So much so that we usually default to using a managed service, such as Amazon SES, SendGrid, Mailgun, etc. We can try to reinvent those, but pain lies that way.

Instead we’ll focus on the application-side machinery surrounding actual email sending.

Durability

In a comms service, the most important goal is durability. We cannot just shoot out emails into the ether and hope for the best, because that’s just sloppy. We need to record the fact. When a request is made to send an email, there should be two eventual outcomes:

- The email does get sent, and that fact gets recorded in our system, so that

- We can inspect and audit sent messages, and link them to our business process

- We know that message was sent and don’t attempt to send it a second time

- The attempt to send results in an error, and that fact gets recorded, so we can act on it, in a manual or automated manner

Specifically, there should be no outcome where our system accepts a request to send a message, and that fact is forgotten - due to external system error, hardware fault, service shutdown in the midst of processing, or any other reason.

The case for messaging middleware

Not losing messages is our top priority. Second on the list is near-realtime processing - a recipient should receive their email shortly after a message was scheduled, for some definition of ‘shortly’. Specifically, this excludes a batch processing implementation. Firing up a task that reads unsent messages from the database every five minutes and sends them in bulk is not adequate.

These durability and near-realtime requirements are crucial to a usecase where not being able to deliver email is deemed a system failure. These are often dubbed “transactional emails” - examples being “Order confirmation”, “Payment receipt”, “Invoice”, “Password reset”. A counter-example would be high-volume messaging to many recipients as part of marketing campaign. In that example, depending on the usecase, both the durability and latency requirements might be relaxed to achieve higher throughput. We’re only discussing transactional emails in this article.

To sum up, our usecase demands a system giving us the capability to produce and consume messages in a durable and near-realtime manner.

A standard and tried approach to implement this usecase is to use a combination of a relational database and a message-oriented middleware such as Kafka, AWS Kinesis, RabbitMQ or such. Roughly, the scheme is

- Upon receiving a request to send out a set of messages, record those in the database, with some initial status, e.g. “Scheduled”.

- Then, publish these to your message broker of choice; and return to the client that the request was “Accepted”

- A consumer of that message topic / queue takes messages, attempts to send them to the SMTP-capable server of choice

- Upon success

- Update message status in the database to “Processed”

- Acknowledges to the message broker the message was processed (in the case of Kafka, by committing the message’s offset)

- Upon error, and failing automated retrial

- Update message status to “Errored”

- acknowledge message in the message broker and move on to the next one.

- Upon success

The errored messages can then be actioned automatically or manually, either via sourcing them from the database state, or sending them to a “Dead letter queue”.

This approach provides at-least-once delivery semantics (which is the best we can do, since deduplication in general cannot be achieved with SMTP), and also fulfils our near-realtime requirement by virtue of using a message bus. Typically, by means of the message bus, it also provides unbounded horizontal scalability - until the RDBMS or the SMTP service becomes the bottleneck.

The cost of messaging middleware

Kafka and friends are great, but they come at some costs. If you’re only introducing messaging middleware in your system now, you will need to acknowledge the costs:

-

Organisational cost: you need everyone on the squad to be familiar with the new technology, and at least a few people proficient in it.

-

Complexity cost: you’re introducing an additional distributed system in your stack. This introduces new programming models, new libraries, new failure modes of the system, and new concerns in infrastructure provisioning and operation.

-

Direct financial cost: at the time of writing, an entry-level 3-node AWS MSK cluster comes out at circa $600 per month, sans tax. For a large enterprise this amounts to an accounting error, but for a frugal startup it is substantial, especially in the early stages of trying to make a service financially viable.

Or maybe you’re one of the few businesses that already owns their hardware, you’ve over-provisioned and have the spare resources, and you’re willing to operate Kafka on your own. This might be a good fit if you already have the expertise.

If not - among other things, you’re now in the business of operating a distributed consensus algorithm in production. Congratulations! Just a reminder that your three-node cluster (or six, if you’re running Raft on dedicated nodes) that’s running fine is one node failure and one network partition away from complete system outage. All this to say, it’s not an endeavour to be taken lightly.

The Cowboy’s way

If we assessed the above costs and disagreed with paying them, where does that leave us? We’re already operating a relational database, so could we build messaging on top of just that? Certainly it’s an unorthodox approach; but there’s a growing “Just use Postgres” sentiment within our industry, and maybe there’s reasoning behind it?

The two major requirements we have towards our solution are durability and near-realtime delivery. And the former is what RDBMS are built for, so we’ve checked that box by construction.

PostgreSQL has a feature called LISTEN / NOTIFY, an asynchronous inter-process communication mechanism. Producers can send messages to a notification channel from within a given session (within a transaction or otherwise), and any consumer currently listening on that channel (again, via a database session) will have the messages broadcasted to them. This gives us a distributed multi-producer, multi-consumer queue.

The catch is, this pub-sub mechanism is not persistent / durable, and therefore has no delivery guarantees whatsoever. It does exactly what is advertised in the documentation - broadcast notifications to whoever is listening at the time. There’s no append-only log of messages behind that, no acknowledgement protocol, and no capability to replay messages. Because of that, multiple failure modes come to mind immediately:

- If a message gets sent, but consumers that we intended it for are currently down, the message is lost

- If a message gets delivered to a consumer, and the consumer crashes after receiving the message and before acting on it, the message is lost

- If a set of messages are to be issued upon commit of a transaction, and the database server crashes after committing the transaction and before sending the messages, the messages are lost

So, our database can provide message durability (but no real-time messaging), and LISTEN / NOTIFY provides real-time, asynchronous messaging (but no durability). It looks like we need to combine both.

Let’s try to do that.

Design goals

Before writing any code, it’s useful to be explicit about what we want to build at a high level, with our stated usecase in mind. Here are our goals, in order of importance:

- At-least-once delivery. As we pointed out, it should never be the case that the system accepts a message and that message is consequently lost.

- Minimise message duplication. Exactly-once delivery is impossible in distributed systems in general, and certainly so when the downstream protocol does not allow for idempotency (which SMTP does not). That being said, we must make an effort to minimise duplication to the extent practically possible. As an example, customers generally freak out when receiving multiple payment confirmations, and that’s going to be bad for business.

- High availability. It must be possible to run multiple producers and multiple consumers at the same time safely, so that

- A single node crashing does not result in service outage

- Zero-downtime deployments are possible.

- We should attempt to optimise the system throughput, but not at the expense of any of the above requirements. Specifically, a design which increases throughput while increasing the chances of message duplication is not fit for our goals.

… But might be an excellent fit for other usecases. We can imagine a payment processing usecase, where the payment gateway allows us to specify an external ID for our payment request. If we attempt to place the same payment multiple times, duplicates will be rejected downstream, hopefully with no side effect. In such a scenario, a design with massive throughput increase at the cost of slight message duplication increase might be a fit one.

Tools of choice

Our implementation language of choice will be Scala. Necessarily, a number of library choices need to be made - I’ve went for tried and tested ones which are suitable for production usage. Notably, for RDBMS connectivity we use skunk, which supports the native PostgreSQL backend / frontend protocol, and has good support for LISTEN / NOTIFY.

I won’t expand more on the libraries used, lest this article turn into a book. For an overview of them, see this piece.

Initial attempt

The general plan is we’ll do some evolutionary prototyping of our service, starting with a very simple sketch that can get us to a rudimentary but passing test suite quick. Then we’ll go back to design goals, add missing features, write performance tests, optimise, rinse and repeat.

We’ll start with the core data types and SQL model for email messaging.

Data model

Email messages have a set of recipients, a subject and a body. For the sake of terseness, we won’t deal with attachments right now.

final case class EmailMessage(

subject: Option[NonEmptyString],

to: List[Email],

cc: List[Email],

bcc: List[Email],

body: Option[NonEmptyString]

)

Above, NonEmptyString is a string with a minimum length of 1, enforced through iron refinement types.

type NonEmpty = MinLength[1]

type NonEmptyString = String :| NonEmpty

object NonEmptyString extends RefinedTypeOps.Transparent[NonEmptyString]

, and Email represents an email address. For the time being that will just be a non-empty string. A production-grade implementation would involve regex matching, which iron allows for.

opaque type Email = NonEmptyString

object Email extends RefinedTypeOps[String, NonEmpty, Email]

Once an email message is scheduled for delivery in our system, it gets an unique identifier.

object EmailMessage:

opaque type Id = Long

Scheduled messages are claimed for processing by a consumer. The processing can either succeed (the message was accepted by the downstream SMTP server), or it can fail.

enum EmailStatus:

case Scheduled, Claimed, Sent, Error

These are all the domain types we’ll work with.Their corresponding PostgreSQL representation is

create type email_status as enum ('scheduled', 'claimed', 'sent', 'error');

create table email_messages(

id bigserial primary key,

subject text,

to_ text[] not null,

cc text[] not null,

bcc text[] not null,

body text,

status email_status,

error text,

created_at timestamptz not null,

last_updated_at timestamptz

);

The “created at” and “updated at” field are useful for audit and monitoring purposes, and will also aid us down the line in ensuring eventual at-least-once delivery.

Database interaction protocol

Our service will consist of two logical components.

- A producer, which will be responsible for receiving new email messages (via HTTP endpoint or other programmatic request), scheduling them for sending, and notifying consumers of the new messages via PostgreSQL

NOTIFY - One or many (see “high-availability”) consumer processes which receive new messages via

LISTEN, claim them for processing, and are then responsible to send them out via SMTP, and record the success or failure of that attempt.

Here’s a set of database-level operations that we’ll use to implement the above.

trait EmailMessageRepo[F[_]]:

def scheduleMessages(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[List[EmailMessage.Id]]

def listen: Stream[F, EmailMessage.Id]

def claim(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Option[EmailMessage]]

def markAsSent(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Boolean]

def markAsError(id: EmailMessage.Id, error: String): F[Boolean]

scheduleMessages is what will be called by the producer. This records new messages in the database, and is also responsible for publishing these to the consumer via NOTIFY, upon transaction success.

listen is the entry point for the consumer, implemented via PG LISTEN, and modelled as an fs2.Stream. Then, for each message received, the consumer

- Attempts to

claimthe message for processing. Note the return type,F[Option[EmailMessage]]. Remember there can be multiple consumers running and the message might have already been claimed by another consumer by the time it’s received, in which case there’s nothing we need to do, and we can move on to the next one. - Sends the message downstream (i.e. SMTP), and records that in the database via

markAsSent. Note the return type,F[Boolean].falseindicates either this message doesn’t exist, or that it’s already been marked as sent (or as error) - in the latter case, we’ve observed more-than-once delivery. - In case of downstream error, we record that in the database via

markAsError. Again, the return type isF[Boolean]andfalsecan indicate duplicate delivery.

Database internals

For completeness, we list a small utility layer around skunk. This gives us

- A function

transactto execute transactions with a bit less boilerplate - A utility function

batchedfor batch insertion - A function

subscribeToChannelto obtain aLISTENsubscription, where the underlying database session is part of the resulting stream’s scope.

package tafto.persist

import cats.implicits.*

import fs2.Stream

import skunk.*

import skunk.data.{Identifier, Notification}

import cats.effect.*

import cats.effect.std.Console

import tafto.config.DatabaseConfig

import fs2.io.net.Network

import natchez.Trace

import cats.data.NonEmptyList

import cats.Applicative

final case class Database[F[_]: MonadCancelThrow](pool: Resource[F, Session[F]]):

def transact[A](body: Session[F] => F[A]): F[A] =

val transactionalSession = for {

session <- pool

transaction <- session.transaction

} yield (session, transaction)

transactionalSession.use { case (session, _) =>

body(session)

}

def subscribeToChannel(channelId: Identifier): Stream[F, Notification[String]] =

Stream.resource(pool).flatMap { session =>

session.channel(channelId).listen(Database.notificationQueueSize)

}

object Database:

// error is raised if query has more than 32767 parameters

// this batch size allows for ~65 query parameters per row, which should be plenty

val batchSize = 500

// this is up to ~80MB memory under the default PG configuration (each message cannot exceed 8000 bytes)

val notificationQueueSize = 10000

def batched[F[_]: Applicative, A, B](

s: Session[F]

)(query: Int => Query[List[A], B])(in: NonEmptyList[A]): F[List[B]] = {

val inputBatches = in.toList.grouped(batchSize).toList

inputBatches

.traverse { xs =>

s.execute(query(xs.size))(xs)

}

.map(_.flatten)

}

def make[F[_]: Temporal: Trace: Network: Console](config: DatabaseConfig): Resource[F, Database[F]] =

Session

.pooled[F](

host = config.host.value,

port = config.port.value,

user = config.userName.value,

password = config.password.value.value.some,

database = config.database.value,

max = 10,

strategy = Strategy.SearchPath

)

.map(Database(_))

We’re ready to implement EmailMessageRepo which we defined above.

final case class PgEmailMessageRepo[F[_]: Clock: MonadCancelThrow](

database: Database[F],

channelId: Identifier

) extends EmailMessageRepo[F]:

scheduleMessages is straightforward:

override def scheduleMessages(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[List[EmailMessage.Id]] =

database.transact { s =>

for

now <- Time[F].utc

result <- Database.batched(s)(EmailMessageQueries.insertMessages)(messages.map { x =>

(x, EmailStatus.Scheduled, now)

})

_ <- notify(s, result)

yield result

}

private def notify(s: Session[F], ids: List[EmailMessage.Id]): F[Unit] =

val channel = s.channel(channelId)

ids.traverse_(x => channel.notify(x.show))

We’re using batch insert to schedule messages to increase producer throughput. On the other hand, we’ve had to publish notifications one by one, which means O(n) network roundtrips for n messages. We’ll revise this later.

Then, our actual insert query is

def insertMessages(size: Int) =

sql"""

insert into email_messages(subject, to_, cc, bcc, body, status, created_at)

values ${insertEmailEncoder.values.list(size)}

returning id;

""".query(emailMessageId)

Nothing notable here.

We’re omitting database codecs (

insertEmailEncoder,emailMessageId), and from here on I’ll skip any other non-essential details. All the code we’ll eventually arrive at is published in a repository linked at the end of this article.

listen is also unremarkable, it creates a database session, issues LISTEN on the corresponding channel id, and decodes the incoming PostgreSQL string payload to EmailMessage.Id.

override val listen: Stream[F, EmailMessage.Id] =

database

.subscribeToChannel(channelId)

.evalMap { notification =>

val payload = notification.value

payload.toLongOption

.toRight(s"Expect EmailMessage.Id, got ${payload}")

.map(EmailMessage.Id(_))

.orThrow[F]

}

Next, on to claim, markAsSent, and markAsError. All these update the status of the corresponding DB row, where

- We should only be able to claim a message if it’s currently scheduled

- We should only mark a message as error or as success it’s currently claimed

The above is a finite state machine. We’ll model it with the following datatype

final case class UpdateStatus private (

id: EmailMessage.Id,

currentStatus: EmailStatus,

newStatus: EmailStatus,

updatedAt: OffsetDateTime

)

object UpdateStatus:

def claim(id: EmailMessage.Id, updatedAt: OffsetDateTime) = UpdateStatus(

id = id,

currentStatus = EmailStatus.Scheduled,

newStatus = EmailStatus.Claimed,

updatedAt = updatedAt

)

def markAsSent(id: EmailMessage.Id, updatedAt: OffsetDateTime) = UpdateStatus(

id = id,

currentStatus = EmailStatus.Claimed,

newStatus = EmailStatus.Sent,

updatedAt = updatedAt

)

def markAsError(id: EmailMessage.Id, updatedAt: OffsetDateTime) = UpdateStatus(

id = id,

currentStatus = EmailStatus.Claimed,

newStatus = EmailStatus.Error,

updatedAt = updatedAt

)

(Equivalently you could encode this as an ADT)

Now we can implement claim in terms of the above:

override def claim(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Option[EmailMessage]] =

Time[F].utc.flatMap { now =>

updateStatusReturning(UpdateStatus.claim(id, now))

}

private def updateStatusReturning(updateStatus: UpdateStatus): F[Option[EmailMessage]] =

database.pool.use { s =>

for

query <- s.prepare(EmailMessageQueries.updateStatusReturning)

result <- query.option(updateStatus)

yield result

}

The corresponding query is

val updateStatusReturning = sql"""

with ids as (

select id from email_messages where id=${emailMessageId} and status=${emailStatus}

for update skip locked

)

update email_messages m set status=${emailStatus}, last_updated_at=${timestamptz}

from ids

where m.id = ids.id

returning subject, to_, cc, bcc, body;

""".query(domainEmailMessageCodec).contramap[UpdateStatus] { updateStatus =>

(updateStatus.id, updateStatus.currentStatus, updateStatus.newStatus, updateStatus.updatedAt)

}

There’s a couple of things above worth expanding on.

- We only update a row if its

idmatches and it has the expectedcurrentStatus, encoding the state machine from above. This helps avoid duplicate claiming, or duplicate marking as sent / error in case of multiple concurrent consumers. select ... for update skip lockedmeans if a message is in the process of being claimed by another consumer and has a row-level lock on it, we’ll skip it without waiting. This makes sense, since chances are it’ll be processed by the other consumer anyway and the wait would have been unnecessary. This eliminates row-level lock contention, and will become handy once we decide to claim multiple messages in a batch.

As pointed out in the

PostgreSQLdocumentation,select ... for update skip lockedcan provide an inconsistent view of the data: if another consumer has locked the row and we skip it, but that consumer’s transaction does not eventually commit, the message will be lost - i.e. it will not have been claimed by any consumer. We will address this later, together with other message loss scenarios.

Lastly, markAsSent and markAsError are implemented in the exact same vein, so we will not review them.

Email sender

We’re not focusing on actual email sending in this article. We just need an interface to work with.

trait EmailSender[F[_]]:

def sendEmail(id: EmailMessage.Id, email: EmailMessage): F[Unit]

A production implementation will require F: MonadError in order to attempt sending email and handle errors accordingly, and MonadCancel and Temporal in order to ensure cancellation and timeout capabilities.

In tests, we’ll mostly be using a mock implementation which always succeeds, and collects sent emails for tests to then inspect.

package tafto.itest.util

import cats.implicits.*

import cats.effect.*

import tafto.domain.EmailMessage

import tafto.service.comms.EmailSender

final case class RefBackedEmailSender[F[_]: Sync](ref: Ref[F, List[(EmailMessage.Id, EmailMessage)]])

extends EmailSender[F]:

override def sendEmail(id: EmailMessage.Id, email: EmailMessage): F[Unit] = ref.update(xs => (id, email) :: xs)

val getEmails: F[List[(EmailMessage.Id, EmailMessage)]] = ref.get.map(_.reverse)

object RefBackedEmailSender:

def make[F[_]: Sync]: F[RefBackedEmailSender[F]] =

Ref.of(List.empty[(EmailMessage.Id, EmailMessage)]).map { ref =>

RefBackedEmailSender(ref)

}

Notes on production implementations

As an aside, some guidance about production implementations of email sending.

-

We want to use HTTP if possible, and favour a SMTP provider that allows for a REST interface. (AWS SES and SendGrid being two such examples.) A direct SMTP integration, though

javax.mailor wrappers, is unfavourable since it’s very likely to introduce resource-unsafe and cancellation-unsafe code. Conversely, an integration built on top ofhttp4s-ember-clienthas resource safety built in, uses NIO, has a well-understood threading and connection pooling model and provides tracing and observability. -

We should use reasonable timeouts, so that an intermittent / occasional set of requests exhibiting pathological latency does not grind the whole system to a halt.

-

We can consider introducing a retry strategy. Here’s a simple example using

cats-retry:

object EmailSender:

def retrying[F[_]: Temporal: Logger](policy: RetryPolicy[F])(underying: EmailSender[F]): EmailSender[F] =

(id, email) => Retry.retrying(policy)(underying.sendEmail(id, email))

package tafto.service.util

import scala.concurrent.duration.*

import retry.*

import cats.Applicative

import cats.effect.Temporal

import io.github.iltotore.iron.*

import io.github.iltotore.iron.constraint.numeric.*

import io.odin.Logger

object Retry:

def fullJitter[F[_]: Applicative](

maxRetries: Int :| Positive,

baseDelay: FiniteDuration

) = RetryPolicies.limitRetries[F](maxRetries) `join` RetryPolicies.fullJitter(baseDelay)

def retrying[F[_]: Temporal: Logger, A](policy: RetryPolicy[F])(fa: F[A]): F[A] =

retryingOnAllErrors[A](

policy = policy,

onError = (error: Throwable, _: RetryDetails) => {

Logger[F].warn(error.getMessage(), error)

}

)(fa)

A production-grade retry strategy will be more involved, differentiating between error cases that are worth retrying and ones which are not. Those will vary depending on your SMTP vendor.

- Depending on the vendor used, your implementation might require client-side rate limiting.

Tying it all together

Using the persistence layer and email sender above, we’re ready for an initial stab at our comms service.

package tafto.service.comms

import tafto.domain.*

import cats.effect.*

import fs2.Stream

import cats.data.NonEmptyList

import cats.implicits.*

import io.odin.Logger

trait CommsService[F[_]]:

// producer

def scheduleEmails(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[List[EmailMessage.Id]]

// consumer

def run: Stream[F, Unit]

object CommsService:

def apply[F[_]: Temporal: Logger](

emailMessageRepo: EmailMessageRepo[F],

emailSender: EmailSender[F],

): CommsService[F] =

new CommsService[F] {

override def scheduleEmails(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[List[EmailMessage.Id]] =

emailMessageRepo.scheduleMessages(messages)

override def run: Stream[F, Unit] =

emailMessageRepo.listen

.evalMap(processMessage)

.onFinalize {

Logger[F].info("Exiting email consumer stream.")

}

private def processMessage(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Unit] =

for

_ <- Logger[F].debug(s"Processing message $id.")

maybeMessage <- emailMessageRepo.claim(id)

_ <- maybeMessage match

case None =>

Logger[F].debug(

s"Could not claim message $id for sending as it was already claimed by another process, or does not exist."

)

case Some(message) =>

for

sendEmailResult <- emailSender.sendEmail(id, message).attempt

_ <- sendEmailResult.fold(markAsError(id, _), _ => markAsSent(id))

yield ()

yield ()

private def markAsSent(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Unit] =

emailMessageRepo

.markAsSent(id)

.flatTap {

case true => ().pure[F]

case false =>

Logger[F].warn(

s"Duplicate delivery detected. Email message $id sent but already marked by another process."

)

}

.void

private def markAsError(id: EmailMessage.Id, error: Throwable): F[Unit] =

for

_ <- Logger[F].error(s"Error when sending message ${id}", error)

wasMarked <- emailMessageRepo.markAsError(id, error.getMessage())

_ <-

if (wasMarked) {

().pure[F]

} else {

Logger[F].warn(s"Could not mark message $id as error, possible duplicate delivery detected")

}

yield ()

}

This already passes a rudimentary suite of tests. Notably, when running multiple consumers concurrently, duplicate delivery is not observed, so long as there is no service crash in between sending an email and marking it as sent. We test this out with 2, 4 and 8 concurrent consumers.

package tafto.itest

import cats.implicits.*

import scala.concurrent.duration.*

import cats.effect.*

import cats.data.NonEmptyList

import io.github.iltotore.iron.*

import io.github.iltotore.iron.constraint.numeric.Positive

import tafto.persist.*

import fs2.*

import weaver.pure.*

import tafto.service.comms.CommsService

import tafto.util.*

import tafto.domain.*

import tafto.itest.util.*

import _root_.io.odin.Logger

object CommsServiceDuplicationTest:

final case class TestCase(

messageSize: Int :| Positive,

parallelism: Int :| Positive

)

val testCases = List(

TestCase(messageSize = 1000, parallelism = 2),

TestCase(messageSize = 1000, parallelism = 4),

TestCase(messageSize = 1000, parallelism = 8)

)

def tests(db: Database[IO])(using

logger: Logger[IO]

): Stream[IO, Test] =

seqSuite(

testCases.map { testCase =>

test(

s"CommsService consumer prevents duplicate message delivery (message size = ${testCase.messageSize}, parallelism = ${testCase.parallelism})"

) {

for

chanId <- ChannelId("comms_dedupe_test").asIO

emailSender <- RefBackedEmailSender.make[IO]

emailMessageRepo = PgEmailMessageRepo(db, chanId)

commsService = CommsService(emailMessageRepo, emailSender)

commsServiceConsumerInstances = Stream

.emits(List.fill(testCase.parallelism)(commsService.run))

.parJoinUnbounded

result <- useBackgroundStream(commsServiceConsumerInstances) {

val msg = EmailMessage(

subject = Some("Asdf"),

to = List(Email("foo@bar.baz")),

cc = List(Email("cc@example.com")),

bcc = List(Email("bcc1@example.com"), Email("bcc2@example.com")),

body = Some("Hello there")

)

val messages = NonEmptyList(

msg,

List.fill(testCase.messageSize - 1)(msg)

)

commsService.scheduleEmails(messages).flatMap { ids =>

for {

sentEmails <- emailSender.waitForIdleAndGetEmails(5.seconds)

} yield expect(sentEmails.size === testCase.messageSize) `and`

expect(sentEmails.map { case (id, _) => id }.toSet === ids.toSet)

}

}

yield result

}

}

)

Preventing message loss

We have a goal to provide eventual at-least-once delivery. To accomplish this, let’s think about the possible failure modes in the current implementation resulting in message loss.

Scheduled messages might never be claimed in at least the following scenarios:

- Consumer unavailable: if a message is scheduled while 0 consumers are available, there will be no listeners on the channel and the message won’t be claimed

- Consumer failure: if an error occurs at consumer-side while attempting to claim a message, and the consumer crashes, that message will never be claimed, unless another consumer is available and able to claim that message

- Database server error or failure: we’ve made sure to send notifications from within a transaction. This does mean notifications won’t be sent out unless the transaction succeeds, but there’s still the possibility that the transaction is committed, and then the database crashes before sending out the notifications - again, these messages will never be claimed.

- Channel failure - it’s possible that a notification is published, but never delivered to a consumer’s session due to network error.

Similarly, claimed messages might never be marked, due to either consumer error or database server error. When that happens, we have no mechanism to pick them up again and they will remain claimed and unprocessed indefinitely.

All these can be addressed by introducing a “time to live” for messages in scheduled and claimed states. The observation being, those states are non-final in our state machine, and under normal operation a message should remain in them for only so long. If a certain threshold elapses, we will assume that one of the above scenarios occurred, and the message needs to be reprocessed.

To do this, at a certain fixed interval we’ll query the database for scheduled and claimed messages past their time to live, and reprocess them. This will ensure that, eventually, every message in the system ends up in either Sent or Error status.

It’s somewhat displeasing that we’ve had to introduce polling to a system that was fully event-driven. On the upside, polling will always have a 0-message backlog to process under normal operation, which will have negligible performance impact. We’ll only do actual work in our polling process when things have gone awry.

Let’s introduce a configuration for time to live and polling interval for scheduled but not claimed and claimed but not processed messages:

final case class ScheduledMessagesPollingConfig(

timeToLive: FiniteDuration,

pollingInterval: FiniteDuration

)

final case class ClaimedMessagesPollingConfig(

timeToLive: FiniteDuration,

pollingInterval: FiniteDuration

)

final case class PollingConfig(

forScheduled: ScheduledMessagesPollingConfig,

forClaimed: ClaimedMessagesPollingConfig

)

object PollingConfig:

val default: PollingConfig = PollingConfig(

forScheduled = ScheduledMessagesPollingConfig(

timeToLive = 1.minute,

pollingInterval = 30.seconds

),

forClaimed = ClaimedMessagesPollingConfig(

timeToLive = 30.seconds,

pollingInterval = 30.seconds

)

)

These values, especially timeToLive, can and should be tweaked in an actual production deployment, according to what latency we expect in the processing of a single message once it’s been scheduled. So what happens if we get these values wrong?

- For both scheduled and claimed messages, if we introduce a TTL that’s too long, we introduce unwanted latency in the processing of a message - but only for messages which were not delivered by our normal LISTEN / NOTIFY scheme, which will be a rare occurrence anyway

- For scheduled messages, if we introduce a TTL that’s too short, we might mistakenly poll for and claim a message which would have been claimed by the normal scheme. This will introduce extra work, but no other problem, since claiming a message is an idempotent operation under the database implementation we presented above.

- For claimed messages, if we introduce a TTL that’s too short, and mistakenly reprocess a claimed message which was already in the process of being processed, we’ll cause duplicate delivery. This means we should pick

forClaimed.timeToLivethat’s comfortably longer than the typical processing of a claimed message we observe in the system. In practice, this can be achieved by making sure that downstream processing (SMTP) has a reasonable client-side timeout. E.g.timeToLive = 30.secondswill in most scenarios be a reasonable timeout if a timeout of5.secondsis enforced downstream.

To the last point, and in any case, duplicate delivery cannot be completely avoided under at-least-once delivery semantics. As a mitigation, later in the article we will introduce and evolve tracing for our system, so we can observe such occurrences and act on them.

With this configuration out of the way, let’s extend our comms service with our new polling scheme.

trait CommsService[F[_]]:

// producer

def scheduleEmails(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[List[EmailMessage.Id]]

// real-time consumer

def run: Stream[F, Unit]

// poll for scheduled messages according to config, and act on them

def pollForScheduledMessages: Stream[F, Unit]

// poll for claimed messages according to config, and act on them

def pollForClaimedMessages: Stream[F, Unit]

// real-time consumer augmented by polling to catch up on any message loss

def backfillAndRun(using c: Concurrent[F]): Stream[F, Unit] =

Stream(pollForScheduledMessages, pollForClaimedMessages).parJoinUnbounded

.concurrently(run)

pollForScheduledMessages will retrieve scheduled messages matching our config, and will broadcast them via NOTIFY back to the corresponding channel, so they can be picked up by our regular run machinery:

override val pollForScheduledMessages: Stream[F, Unit] =

Stream.fixedRateStartImmediately(pollingConfig.forScheduled.pollingInterval).evalMap { _ =>

for

now <- Time[F].utc

scheduledIds <- emailMessageRepo

.getScheduledIds(now.minusNanos(pollingConfig.forScheduled.messageAge.toNanos))

_ <- emailMessageRepo.notify(scheduledIds)

yield ()

}

, where getScheduledIds has the underlying query

sql"""

select id from email_messages where status = ${emailStatus} and created_at <= ${timestamptz};

"""

.query(emailMessageId)

.contramap[OffsetDateTime] { case createdAt => (EmailStatus.Scheduled, createdAt) }

pollForClaimedMessages has the same database implementation (using updatedAt instead of createdAt). Each message is then reprocessed in the same way messages claimed by the non-polling machinery are.

override val pollForClaimedMessages: Stream[F, Unit] =

Stream.fixedRateStartImmediately(pollingConfig.forClaimed.pollingInterval).evalMap { _ =>

for

now <- Time[F].utc

claimedIds <- emailMessageRepo.getClaimedIds(now.minusNanos(pollingConfig.forClaimed.timeToLive.toNanos))

_ <- claimedIds.traverse(reprocessClaimedMessage)

yield ()

}

private def reprocessClaimedMessage(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Unit] = for

msg <- emailMessageRepo.getMessage(id)

result <- msg.fold {

Logger[F].warn(s"Could not reprocess claimed message with id $id as it was not found")

} { case (message, status) =>

if status === EmailStatus.Claimed then processClaimedMessage(id, message)

else

Logger[F].debug(

s"Will not reprocess message with id $id as it's no longer claimed, current status is $status"

)

}

Assessing initial throughput

The astute reader might have already spotted ample opportunities for optimisation in our initial implementation. Before trying to make things faster, let’s first figure out how slow they currently are by creating a load test harness.

We’ll start with a load test that collocates the test (producer), code under test (consumer) and database on the same machine, so that it can be easily run on a local development environment without requiring external infrastructure. This is a good enough start to get a feel for performance.

On the other hand, we’re aware this approach can skew test results in various ways

- Distribution of available compute resources across the producer, consumer and database might be unfair, for example the service code might hog CPU and underpower the database, or vice versa

- Eliminating remote networking overhead between the database and the application code might not be representative of a real-world deployment

To address this, we’ll make sure our code is modular enough so that the system, database and test can be distributed to separate physical nodes later.

The load test itself will be a simple scala executable. To measure throughput, we’ll trace our code via the natchez tracing library, and store tracing data in Honeycomb, where we can aggregate, report and graph our test results.

Local tests will be run on a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-1260P × 16 CPU, with 64GB RAM, running Linux 6.13.0 or newer.

Tracing

In the current implementation of CommsService, each message received is decoded and then processed via processMessage. Furthermore, messages are processed in sequence. This means the sum of time spent in processMessage gives us a very good approximation of the total time the consumer takes to process N messages.

We will create a new root natchez.Span for each invocation of processMessage. In order to do so, we introduce the type

type SpanLocal[F[_]] = cats.mtl.Local[F, Span[F]]

, and require natchez.EntryPoint and SpanLocal constraints when constructing CommsService

object CommsService:

def apply[F[_]: Temporal: Logger: Trace: EntryPoint: SpanLocal]

Now we can trace our function of interest in its own root span.

private def processMessage(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Unit] =

val ep = summon[EntryPoint[F]]

// create a new root span

ep.root("processMessage").use { root =>

// the program to trace

val result = for

_ <- Trace[F].put("id" -> id)

_ <- Logger[F].debug(s"Processing message $id.")

maybeMessage <- emailMessageRepo.claim(id)

_ <- maybeMessage match

case None =>

Logger[F].debug(

s"Could not claim message $id for sending as it was already claimed by another process, or does not exist."

)

case Some(message) =>

processClaimedMessage(id, message)

yield ()

// set the program's root span via `cats.mtl.Local.scope`

Local[F, Span[F]].scope(result)(root)

}

Additionally, we add some tracing info to the functions throughout PgEmailMessageRepo, like so

override def claim(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[Option[EmailMessage]] =

span("claim")("id" -> id) {

Time[F].utc.flatMap { now =>

updateStatusReturning(UpdateStatus.claim(id, now))

}

}

These all call into the database using the skunk library, which is also traced in very good detail. This gives us enough data to start building our test.

The

SpanLocal,EntryPointandTraceconstraints will be fulfilled by constructing our final program inKleisliinstead of plainIOtype TracedIO[A] = Kleisli[IO, Span[IO], A]

Test database

We’ll use testcontainers-scala in order to provision a database for tests. This will use docker under the hood.

First, we need to make sure we’re using a recent enough PostgreSQL version

val imageName = DockerImageName.parse("postgres:17.1").asCompatibleSubstituteFor("postgres")

Secondly, for performance purposes, testcontainers sets PostgreSQL write-ahead log fsync option to off. This allows for faster database commits at the expense of throwing away data durability guarantees.

This default only makes sense in unit tests. In our case, it’s going to falsify test results, as it’s not representative of real-world usage. We need to reset the option back to its default.

val container = PostgreSQLContainer(dockerImageNameOverride = imageName)

container.configure { c =>

// as opposed to setCommand("postgres", "-c", "fsync=off");

c.setCommand("postgres")

}

Email sender

Our test is intended to give an upper bound on system throughput - we won’t actually be sending out emails (and if we did, we’d immediately get flagged as spam). To that end, let’s provide a stub instance that does nothing and always succeeds.

package tafto.loadtest.comms

import cats.Applicative

import cats.implicits.*

import tafto.domain.EmailMessage

import tafto.service.comms.EmailSender

final case class NoOpEmailSender[F[_]: Applicative]() extends EmailSender[F]:

override def sendEmail(id: EmailMessage.Id, email: EmailMessage): F[Unit] = ().pure[F]

Load test scenario

Our scenario will

- Spin up a PostgreSQL server via

testcontainers-scala - Apply our database schema to it

- Instantiate a

CommsServiceinstance for our message producer. The producer will use its own separate database pool, and its own Honeycomb settings (service name), so that we can differentiate between producer and consumer spans when querying the test results. - Instantiate a

CommsServicefor the consumer. The consumer will use its own database pool and Honeycomb settings. - Start the consumer, by calling

commsService.backfillAndRun - Perform a warmup of the JVM and the consumer and producer database connection pools, by issuing a number of

SELECT 1statements in parallel for each pool - Publish 5000 test messages via the producer

Below is a full listing of the test scenario:

package tafto.loadtest.comms

import cats.data.{Kleisli, NonEmptyList}

import cats.effect.std.UUIDGen

import cats.effect.{IO, IOApp, Resource}

import cats.implicits.*

import io.github.iltotore.iron.*

import io.odin.Logger

import natchez.EntryPoint

import natchez.mtl.given

import natchez.noop.NoopSpan

import tafto.db.DatabaseMigrator

import tafto.domain.*

import tafto.log.defaultLogger

import tafto.persist.*

import tafto.service.comms.CommsService

import tafto.service.comms.CommsService.PollingConfig

import tafto.testcontainers.*

import tafto.util.tracing.*

object CommsServiceLocalLoadTest extends IOApp.Simple:

given logger: Logger[TracedIO] = defaultLogger

given ioLogger: Logger[IO] = defaultLogger

val makeTestResources: Resource[TracedIO, TestResources] =

for

// starts the PostgreSQL docker container, making sure `fsync` is not `off`

containers <- Containers.make(ContainersConfig.loadTest).mapK(Kleisli.liftK)

config = containers.postgres.databaseConfig

// applies database schema to the database

_ <- Resource.eval(DatabaseMigrator.migrate[TracedIO](config))

// connection pool for the producer. 10 max connections in total

commsDb <- Database.make[TracedIO](config)

// connection pool for the consumer. 10 max connections in total

testDb <- Database.make[TracedIO](config)

// unique identifier of this test run, so we can query test results for a specific run

testRunUUID <- Resource.eval(UUIDGen[TracedIO].randomUUID)

tracingGlobalFields = Map("test.uuid" -> testRunUUID.toString())

// Honeycomb settings for consumer

commsEp <- honeycombEntryPoint[TracedIO](

serviceName = "tafto-comms",

globalFields = tracingGlobalFields

)

// Honeycomb settings for producer

testEp <- honeycombEntryPoint[IO](serviceName = "tafto-load-tests", globalFields = tracingGlobalFields).mapK(Kleisli.liftK)

channelId <- Resource.eval(PgEmailMessageRepo.defaultChannelId[TracedIO])

commsService =

given EntryPoint[TracedIO] = commsEp

val emailRepo = PgEmailMessageRepo(commsDb, channelId)

CommsService(emailRepo, new NoOpEmailSender[TracedIO], PollingConfig.default)

testCommsService =

given EntryPoint[TracedIO] = testEp.mapK(Kleisli.liftK)

val testEmailRepo = PgEmailMessageRepo(testDb, channelId)

CommsService(testEmailRepo, new NoOpEmailSender[TracedIO], PollingConfig.default)

yield TestResources(

commsService = commsService,

commsDb = commsDb,

testCommsService = testCommsService,

testDb = testDb,

testEntryPoint = testEp

)

def publishTestMessages(testResources: TestResources, testSize: Int): IO[Unit] =

val msg = EmailMessage(

subject = Some("Hello there"),

to = List(Email("foo@example.com")),

cc = List(Email("bar@example.com")),

bcc = List(Email("bar@example.com")),

body = Some("General Kenobi!")

)

val msgs = NonEmptyList(msg, List.fill(testSize - 1)(msg))

val result = testResources.testCommsService.scheduleEmails(msgs)

testResources.testEntryPoint.root("scheduleTestMessages").use { span =>

result.run(span).void

}

def warmup(db: Database[TracedIO], name: String): IO[Unit] =

val healthService = PgHealthService(db)

val result = (1 to 50).toList.parTraverse_(_ => healthService.getHealth)

for

_ <- Logger[IO].info(s"Warming up $name")

_ <- result.run(NoopSpan())

_ <- Logger[IO].info(s"Warmup finished: $name")

yield ()

override def run: IO[Unit] =

makeTestResources.mapK(withNoSpan).use { testResources =>

val warmups = List(

warmup(testResources.commsDb, "comms service database pool"),

warmup(testResources.testDb, "test database pool")

).parSequence

val test = testResources.commsService.backfillAndRun.compile.drain.run(NoopSpan()).background.use { handle =>

for

_ <- Logger[IO].info("publishing test messages ...")

_ <- publishTestMessages(testResources, testSize = 5000)

_ <- Logger[IO].info("published test messages.")

_ <- handle.flatMap(_.embedError)

yield ()

}

warmups >> test

}

final case class TestResources(

commsDb: Database[TracedIO],

commsService: CommsService[TracedIO],

testCommsService: CommsService[TracedIO],

testDb: Database[TracedIO],

testEntryPoint: EntryPoint[IO]

)

Results

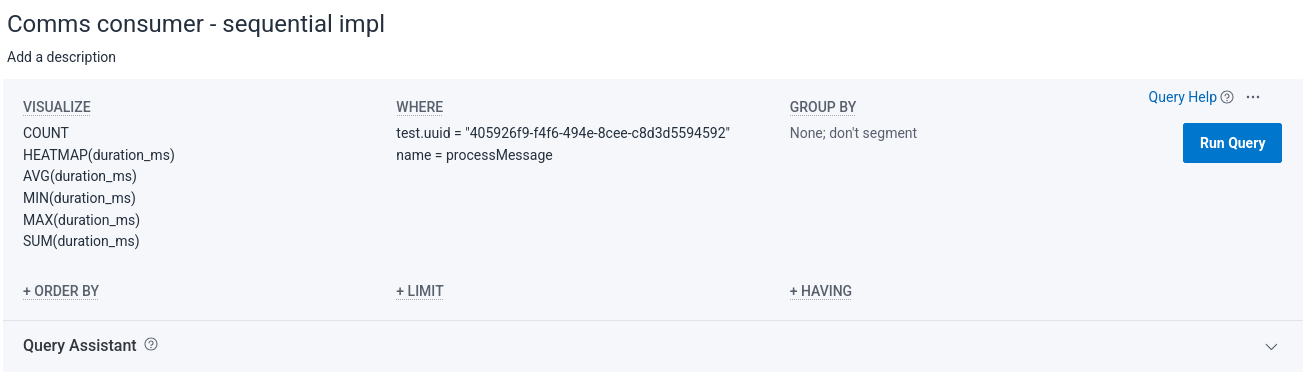

On the consumer side, using this query

we get

On average, we process a single message in 12.3528 ms, so our throughput is 80.95 messages / s. Not impressive at all, but this is our first shot, so we will not despair.

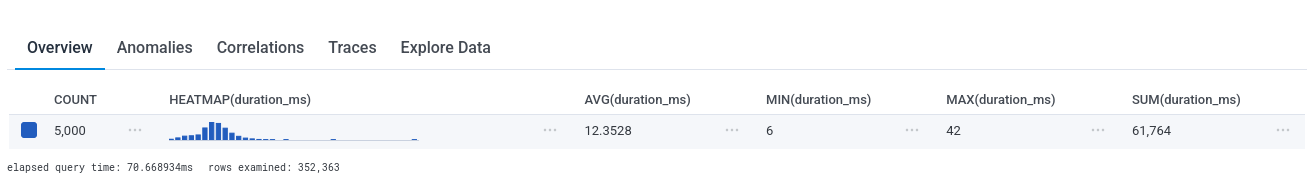

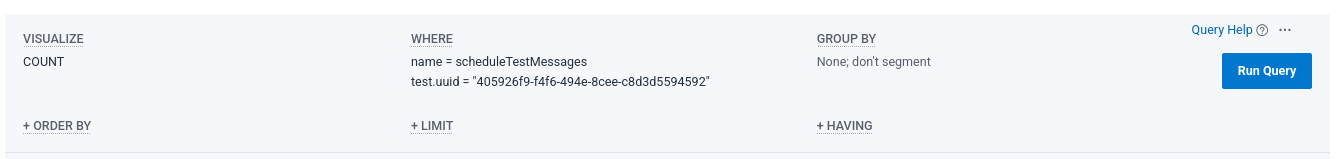

In the producer, there’s a single trace / root span which captures all the work, so we don’t need to perform any aggregations.

We can simply look at that individual trace:

Using a database insertion batch size of 500, scheduling 5000 messages took 2681 ms, which means we were producing 1864.9 messages / s.

Out of the total 2681 ms, 1897 ms or 70% of the total time were spent in NOTIFY. This confirms our suspicion issuing notifications in sequence for each message is not great - and it might be worse in a real deployment, where network latency will be involved.

Improving throughput

Batching of notifications

To reduce the amount of NOTIFY commands we need to issue for a set of messages, we can batch multiple message IDs in a single NOTIFY payload. This will also give us the freedom to process a notification batch in parallel in the consumer.

Since NOTIFY and LISTEN expose a String payload, let’s introduce a type to encode and decode data to / from String.

trait ChannelEncoder[A]:

def encode(a: A): String

trait ChannelDecoder[A]:

def decode(x: String): Either[String, A]

For encoding a list of message ids, for now we’ll just use a comma-separated representation.

object ChannelEncoder:

val emailMessageIds: ChannelEncoder[List[EmailMessage.Id]] = xs => xs.mkString(",")

Similarly, to decode, we split the payload into individual segments, decode to int and construct a message id.

object ChannelDecoder:

val emailMessageIds: ChannelDecoder[Chunk[EmailMessage.Id]] = x =>

val segments = x.split(",")

Chunk

.array(segments)

.traverse(segment =>

val num = segment.toLongOption.toRight(s"$segment is not an integer.")

num.map(n => EmailMessage.Id(n))

)

Next, we’ll update the type of EmailMessageRepo.listen to match the new wire format

def listen: Stream[F, Chunk[EmailMessage.Id]]

In PgEmailMessageRepo, we implement batching of notifications in LISTEN / NOTIFY. We need to be mindful of batch size since maximum payload size of NOTIFY is limited.

// payload must be less than 8000 bytes under default PG configuration

// long max value is 19 digits, this plus comma separator is 20 bytes in utf-8

// this means we must send less than 400 messages. 350 leaves some leeway.

private val notifyBatchSize = 350

If in the future we want to overcome this limitation, we’d need to introduce an intermediate table to store notification payloads, perhaps as JSON.

Let’s update the def listen and def notify implementations:

private def notify(s: Session[F], ids: List[EmailMessage.Id]): F[Unit] =

span("notify")("payload.size" -> ids.size) {

val channel = s.channel(channelId)

ids.grouped(notifyBatchSize).toList.traverse_(xs => channel.notify(ChannelEncoder.emailMessageIds.encode(xs)))

}

// ...

override val listen: Stream[F, Chunk[EmailMessage.Id]] =

database

.subscribeToChannel(channelId)

.evalMap { notification =>

val payload = notification.value

ChannelDecoder.emailMessageIds

.decode(payload)

.orThrow[F]

}

Lastly, CommsService:

override def run: Stream[F, Unit] =

emailMessageRepo.listen

.flatMap(xs =>

Stream.evalUnChunk(

summon[EntryPoint[F]].root("processChunk").use { root =>

val result = Trace[F].put("payload.size" -> xs.size) >>

xs.parTraverse(processMessage)

Local[F, Span[F]].scope(result)(root)

}

)

)

.onFinalize {

Logger[F].info("Exiting email consumer stream.")

}

The root span moves from processMessage to processChunk, and processChunk processes messages in the chunk in parallel. Note parTraverse introduces unbounded parallelism, but that’s in effect throttled by the underlying database connection pool which is bounded.

Running our test again gives us

- 720 ms in the producer, a throughput of 6944.44 messages / s.

- A sum of 6789 ms for

processChunkin the consumer, approximately 736.5 messages / s.

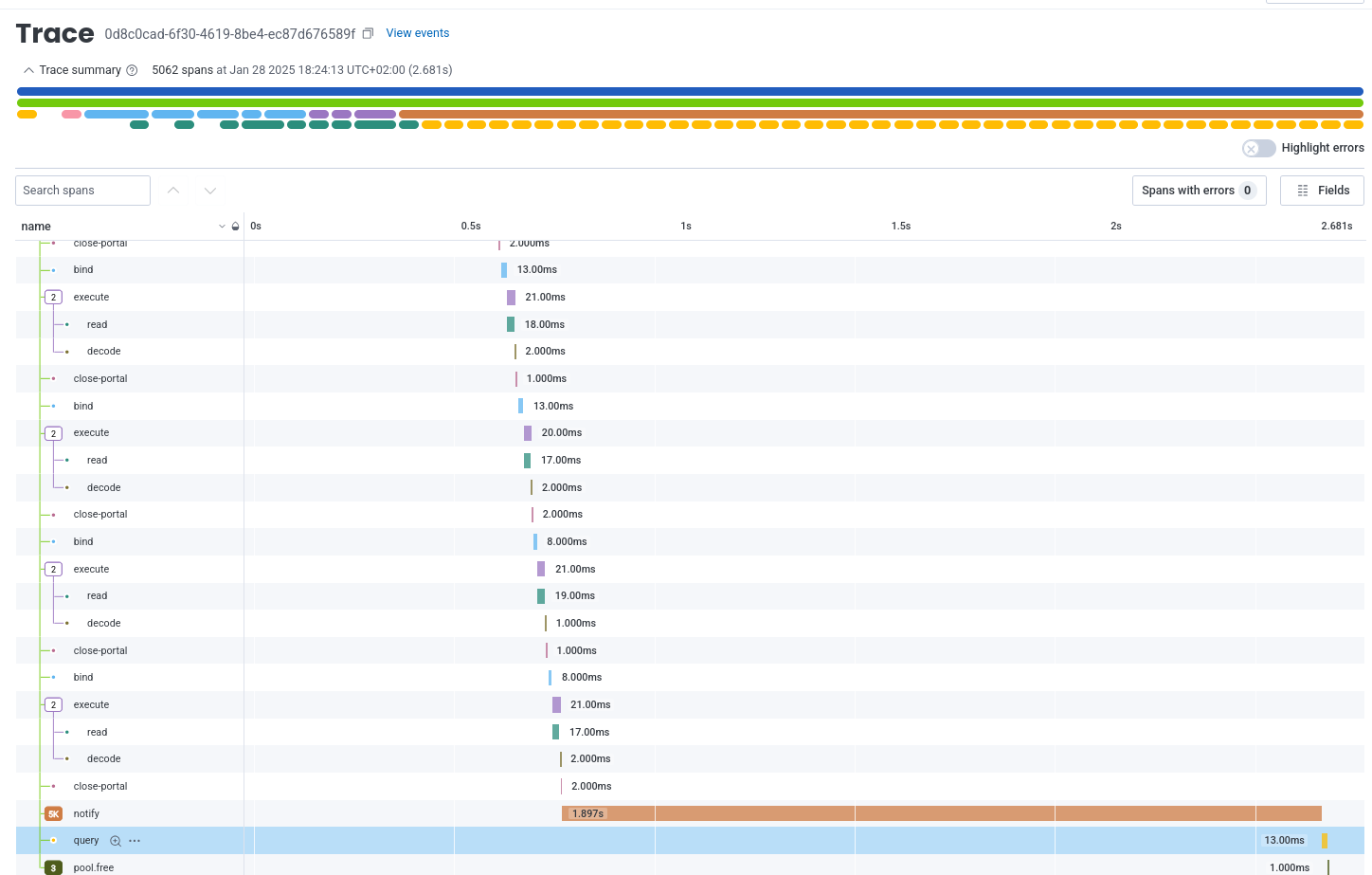

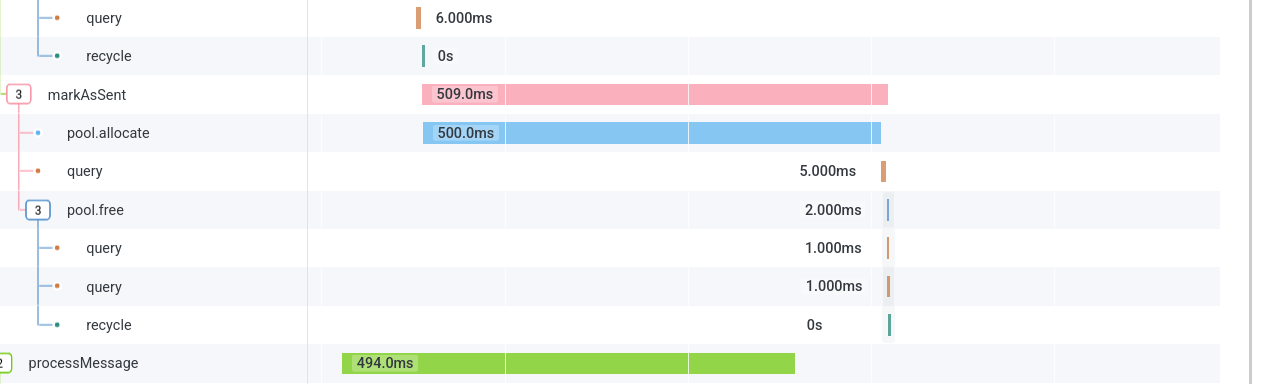

Running htop at the time of running the test shows the system is underutilised in terms of CPU and memory. Looking at some of the slowest consumer traces, we reveal a lot of time is spent in pool.allocate:

This is expected, since parTraverse launches a large amount of fibers that end up waiting for database connections. In aggregate, 1740 seconds are spent waiting in pool.allocate.

Increasing pool size

If the system resources are underutilised, and we see contention for database connections in the consumer, we would expect increasing database pool size to increase throughput, until a certain point. After that, the database sessions themselves will contend for shared resources and throughput will start to decrease again.

Right now database pool size is hardcoded to 10, let’s make it configurable.

final case class TestConfig(

poolSize: Int :| Positive,

testPoolSize: Int :| Positive

)

object TestConfig:

val load: ConfigValue[Effect, TestConfig] =

(

env("POOL_SIZE")

.as[Int :| Positive]

.default(32),

env("TEST_POOL_SIZE")

.as[Int :| Positive]

.default(10)

).mapN { (poolSize, testPoolSize) =>

TestConfig(

poolSize = poolSize,

testPoolSize = testPoolSize

)

}

With a few consecutive test runs, we obtain the following results:

- 6675 ms aggregate consumer time with pool size = 16

- 5607 ms, pool size = 32

- 5452 ms, pool size = 32

- 4936 ms, pool size = 64

- 5147 ms, pool size = 64

- 5124 ms, pool size = 85

Having a pool size of 32, twice the CPU count, seems to be an improvement over a pool size of 10. We’ll settle for that for the time being. In a high availability scenario of 2 instances running, that will be 64 connections in total, which gives a comfortable leeway before hitting PostgreSQL’s default limit of 100 connections.

We’re now seeing consumer throughput of around 1000 messages / s.

Batching message claiming

An obvious source of inefficiency is the fact we’re executing a database query per message

- To claim the message

- To mark the message as sent or errored

It should be safe for the consumer to claim multiple messages at once, and then start processing them. If the service crashes before finishing the whole batch, any outstanding messages will then be picked up by pollForClaimedMessages, once their TTL expires.

The caveat in claiming a batch of messages is we need to the process the whole batch before its TTL expires, or else we can observe duplicate delivery, once the regularly scheduled pollForClaimedMessages kicks in. In other words, it’s now the case that ClaimedMessagesPollingConfig.timeToLive applies to the whole batch.

First we modify PgEmailMessageRepo with the ability to claim multiple messages at once

override def claim(ids: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage.Id]): F[List[(EmailMessage.Id, EmailMessage)]] =

span("claim")("payload.size" -> ids.size) {

Time[F].utc.flatMap { now =>

val updateStatus = UpdateStatus.claim(now)

database.transact { s =>

val inputBatches = ids.grouped(Database.batchSize).toList

inputBatches

.traverse { xs =>

s.execute(EmailMessageQueries.updateStatusesReturning(xs.size))(xs.toList, updateStatus)

}

.map(_.flatten)

}

}

}

(The above will execute a single batch in practice, since the notification batch size happens to be smaller than the database batch size).

The updated database query becomes

def updateStatusesReturning(n: Int) = sql"""

with ids as (

select id from email_messages where id in (${emailMessageId.list(n)}) and status=${emailStatus}

for update skip locked

)

update email_messages m set status=${emailStatus}, updated_at=${timestamptz}

from ids

where m.id = ids.id

returning m.id, m.subject, m.to_, m.cc, m.bcc, m.body;

"""

.contramap[(List[EmailMessage.Id], UpdateStatus)] { (xs, x) =>

(xs, x.currentStatus, x.newStatus, x.updatedAt)

}

.query(emailMessageId ~ domainEmailMessageCodec)

As part of the update to CommsService, we’ll enhance tracing to report on any instances of duplicate delivery. In order to do so, we’ll introduce a datatype describing possible message processing outcomes

package tafto.service.comms

import tafto.domain.{EmailMessage, EmailStatus}

enum MessageProcessingResult(val id: EmailMessage.Id):

// message id could not be claimed - Not an error because it could have been claimed by another process

case CouldNotClaim(override val id: EmailMessage.Id) extends MessageProcessingResult(id)

// message was sent downstream, and was marked successfully. If `error` is present, there was a downstream error.

case Marked(override val id: EmailMessage.Id, error: Option[Throwable]) extends MessageProcessingResult(id)

// message was sent downstream, but was not marked successfully. If `error` is present, there was a downstream error.

// This case indicates possible duplicate delivery.

case CouldNotMark(override val id: EmailMessage.Id, error: Option[Throwable]) extends MessageProcessingResult(id)

// message id from claimed messages reprocessing backlog not found. This is an error that indicates a bug in the system.

case CannotReprocess_NotFound(override val id: EmailMessage.Id) extends MessageProcessingResult(id)

// message from claimed messages reprocessing backlog no longer has status claimed. This is not an error as it might

// have been reprocessed by another process.

case CannotReprocess_NoLongerClaimed(override val id: EmailMessage.Id, newStatus: EmailStatus)

extends MessageProcessingResult(id)

We’ll update CommsService to claim a batch of messages at once; to utilise MessageProcessingResult and to log and trace message processing outcomes consistently, in a single place.

def apply[F[_]: Temporal: Parallel: Logger: TraceRoot](

emailMessageRepo: EmailMessageRepo[F],

emailSender: EmailSender[F],

pollingConfig: PollingConfig

): CommsService[F] =

new CommsService[F]:

override def scheduleEmails(messages: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage]): F[NonEmptyList[EmailMessage.Id]] =

emailMessageRepo.scheduleMessages(messages)

override def run: Stream[F, Unit] =

emailMessageRepo.listen

.flatMap(messages => Stream.evalSeq(processMessages(messages.payload)))

.evalMap(traceAndLog)

.onFinalize {

Logger[F].info("Exiting email consumer stream.")

}

private def processMessages(messageIds: NonEmptyList[EmailMessage.Id]): F[List[MessageProcessingResult]] =

TraceRoot[F].inRootSpan("processChunk") {

for

_ <- Trace[F].put("payload.size" -> messageIds.size)

claimedMessages <- emailMessageRepo.claim(messageIds)

claimedIds = claimedMessages.map { case (id, _) => id }.toSet

notClaimed: List[MessageProcessingResult] = messageIds

.filterNot(claimedIds.contains)

.map(MessageProcessingResult.CouldNotClaim.apply)

results <- claimedMessages.parTraverse { (id, message) =>

processClaimedMessage(id, message)

}

_ <- Trace[F].put("result.size" -> results.size)

yield notClaimed ++ results

}

private def processClaimedMessage(id: EmailMessage.Id, message: EmailMessage): F[MessageProcessingResult] =

for

sendEmailResult <- emailSender.sendEmail(id, message).attempt

result <- sendEmailResult.fold(markAsError(id, _), _ => markAsSent(id))

yield result

private def markAsSent(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[MessageProcessingResult] =

emailMessageRepo

.markAsSent(id)

.map {

case true => MessageProcessingResult.Marked(id, error = None)

case false => MessageProcessingResult.CouldNotMark(id, error = None)

}

private def markAsError(id: EmailMessage.Id, error: Throwable): F[MessageProcessingResult] =

emailMessageRepo.markAsError(id, error.getMessage()).map {

case true => MessageProcessingResult.Marked(id, error = error.some)

case false => MessageProcessingResult.CouldNotMark(id, error = error.some)

}

override val pollForScheduledMessages: Stream[F, Unit] =

Stream.fixedRateStartImmediately(pollingConfig.forScheduled.pollingInterval).evalMap { _ =>

for

now <- Time[F].utc

scheduledIds <- emailMessageRepo

.getScheduledIds(now.minusNanos(pollingConfig.forScheduled.messageAge.toNanos))

_ <- NonEmptyList.fromList(scheduledIds).traverse_(emailMessageRepo.notify)

yield ()

}

override val pollForClaimedMessages: Stream[F, Unit] =

Stream.fixedRateStartImmediately(pollingConfig.forClaimed.pollingInterval).evalMap { _ =>

for

now <- Time[F].utc

claimedIds <- emailMessageRepo.getClaimedIds(now.minusNanos(pollingConfig.forClaimed.timeToLive.toNanos))

_ <- claimedIds.traverse_(reprocessClaimedMessage >=> traceAndLog)

yield ()

}

private def reprocessClaimedMessage(id: EmailMessage.Id): F[MessageProcessingResult] =

TraceRoot[F].inRootSpan("reprocessClaimedMessage") {

for

msg <- emailMessageRepo.getMessage(id)

result <- msg.fold {

MessageProcessingResult.CannotReprocess_NotFound(id).pure[F]

} { case (message, status) =>

if status === EmailStatus.Claimed then processClaimedMessage(id, message)

else MessageProcessingResult.CannotReprocess_NoLongerClaimed(id, status).pure[F]

}

yield result

}

private def traceAndLog(x: MessageProcessingResult): F[Unit] = for

_ <- Trace[F].put("id" -> x.id)

_ <- x match

case MessageProcessingResult.CouldNotClaim(id) =>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.type" -> "CouldNotClaim") >>

Logger[F].debug(s"Could not claim message $id, it may have been claimed by another process.")

case MessageProcessingResult.Marked(id, maybeError) =>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.type" -> "Marked") >>

maybeError.traverse_(traceAndLogEmailError(id, _))

case MessageProcessingResult.CouldNotMark(id, maybeError) =>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.type" -> "CouldNotMark") >>

maybeError.traverse_(traceAndLogEmailError(id, _)) >>

Logger[F].warn(s"Could not mark message $id as processed, possible duplicate delivery detected!")

case MessageProcessingResult.CannotReprocess_NotFound(id) =>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.type" -> "CannotReprocess_NotFound") >>

Logger[F].error(s"Message $id due to be reprocessed was not found!")

case MessageProcessingResult.CannotReprocess_NoLongerClaimed(id, newStatus) =>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.type" -> "CannotReprocess_NoLongerClaimed") >>

Trace[F].put("processing.result.newStatus" -> newStatus.toString()) >>

Logger[F].debug(

s"Message $id due to be reprocessed is no longer claimed, new status is $newStatus, skipping."

)

yield ()

private def traceAndLogEmailError(id: EmailMessage.Id, error: Throwable): F[Unit] = for

_ <- Logger[F].warn(s"Error sending email $id", error)

_ <- Trace[F].put("email.error" -> error.getMessage())

yield ()

We also increase our test size from 5000 to 20000, hopefully smoothing out result variance a bit.

We consume 20000 messages in 5776 ms, a throughput of 3462 messages / s. This is an above 3x increase from our previous implementation, which is surprising at a first glance, since we cut down the database operations by less than 1/2. I think what’s happening is we’re seeing the effect of cutting down the COMMIT operations by around 1/2. That part is I/O heavy, since COMMIT needs to write to the PG write-ahead log, and physically force those writes to the disk.

We might be tempted to batch

markAsErrorandmarkAsSentin the way we batched message claiming, and get an easy shot of dopamine and yet shinier numbers. We’re reluctant to do that just yet, because we suspect it has the potential to increase duplicate deliveries in the event of service shutdown mid-processing.

Next steps

So far, we’ve empirically shown that that near-realtime, highly available messaging with at-least-once delivery semantics is feasible on top of just PostgreSQL.

The throughput observed so far hints the system is usable in a wide set of practical scenarios. I expect we’ll be able to increase it further - after all, we’ve only picked low-hanging fruit so far.

More work remains in the area of performance, as well as correctness.

In the next episode, we’ll try to answer the below questions:

- Our system currently relies on message batching at the producer side in order to achieve the demonstrated throughput. If we instead schedule our message backlog one by one, we will see a drastic decrease. How can we overcome this, and make the system useful in a wider set of scenarios?

- Related to the above, can we further increase parallelism in the consumer, and how will that impact performance? Right now we employ unbounded parallelism within a notification batch, but each batch is processed sequentially, even when multiple batches are available to process at a given point in time.

- The latter will pose a new problem in measuring system performance - it’s currently the case that total processing time equals the sum of each batch’s processing time, but this will no longer be the case if we consume batches in parallel. What changes in tracing do we need to implement to address this?

- There exist common scenarios which can cause duplicate delivery. In some of these, such as service crash or hardware failure mid-processing, there’s nothing we can do. Others, such as graceful

SIGTERM, need to be looked at and tested. - Our load testing infrastructure is pretty basic, as it uses a local development environment, and collocates all components on the same physical machine. It will be useful to employ cloud compute and measure test results there.

Thank you, kind reader, for your time, and stay tuned for the next instalment. Until then, stay curious!

You can find the code presented in this article here. That’s commit 05be95df4d0ad092ef785fa5c156fdfe8f4b1f66.